By Ashley Rella

It has only been in the last few decades that our palates have turned away from aspic jiggly and gooey loving dishes to rubbery, and firm bites. Maybe it’s because of foodborne illnesses that have made our institutional recommendations on internal cooking temperatures to cook the hell out of your food until it’s dry, grainy, and tough. Maybe it’s because processed food-like products had to be shelf-stable and therefore become a monolithic dry texture. Everywhere else in the world slimy, gooey, and silky foods are revered for their flavor, texture, and health benefits. Why don’t we?

Okra, (Ladyfingers, Bhindi, Ngombo) the heat-loving crop of African origins is one of the most polarized vegetables we have in the south. You either really love it in all ways, or you fold your arms up, turn your head, pierce your lips, and refuse to have anything to do it.

Okra, (Ladyfingers, Bhindi, Ngombo) the heat-loving crop of African origins is one of the most polarized vegetables we have in the south. You either really love it in all ways, or you fold your arms up, turn your head, pierce your lips, and refuse to have anything to do it.

Okra arrived from Africa to the Americas through the slave trade. Like many seeds of sacred motherland plants, okra seeds were once braided into women and children’s hair to ensure that if they were captured or forced into slavery they would have means of survival both physically and culturally. It was a continued practice once on American soil and how crops were transferred from plantations across the south.

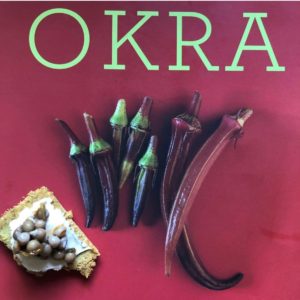

Chris Smith’s book: Okra a Seed to Stem Celebration was the inspiration for this okra flour cracker with okra seeds on top! Yum.

In many cultures, okra has been used in a variety of ways. Old pods are dried and turned into pulp for paper. Seeds can be roasted and used as a coffee substitute. But primarily it used in cooking. Last year I found myself playing around with okra seeds again. A bonus of being closely adjacent to seed gardens. In this instance, I dried ground and turned pods into a flour that I used to make crisps. Then braised matured seeds and placed on top of herbed cheese spread to snack on (pictured left).

Tomato and Okra Tart

The luxurious mucilage found in the walls of okra is an extremely beneficial fiber and lubricant for the digestive system. Making okra a great healthy addition to the diet. Those sticky properties have made it a go-to in recipes where thickening was desired. Its grass-like flavor reminds me of if a green bean and eggplant made a baby and asparagus raised it. The texture can be crunchy when raw, crispy when roasted, or tender if stewed.

If you are hung up on the slime, then acid and dry heat are your solutions. Adding an acid like tomatoes or vinegar (pickling) helps to break it down. And if that is your entry point to becoming an okra lover, then I say go for it!

Traditionally and rightfully so, you can find recipes for okra cooked with tomatoes, corn (cornmeal), soups, and stews. It pairs perfectly with all of its companion summer crops which I believe is one of nature’s gifts to us.

Ghee Roasted Okra with Zataar Spices

If you are looking for some inspiration on how to use your okra this season take a look at these two recipes for Bamiya tahbikh (Sudanese Okra stew) and Spicy Shrimp & Okra. Some of my favorite ways to have or prepare okra:

- Tossed in ghee, roasted or grilled as a side dish

- Cornmeal batter fried with a creamy dipping sauce

- Pickled and tossed with hot spices as a condiment or served with rice

- Okra kimchi (fermented spicy okra)

- In gumbos or stews

- Cornmeal dusted and cast-iron roasted

- Stewed with tomatoes and onions

- Candied raw okra (this is a new favorite)

We know that the south has a rich, brutal, and complicated history. Complicated mostly because for some time only certain (white) people got to write the books and tell the stories, therefore, taking the credit of Black skill and knowledge. But plants and recipes speak of tradition and culture in ways that words never will. We really do know who the experts were in the fields and the kitchens down here whether some choose to acknowledge it or not. Southern food was not created on American land in antebellum homes, it already existed in African and Indigenous kitchens.

We have a (not-so-secret) goal down here in the south to tell okra stories, convert so-called haters, and make okra a sexy addition to plates everywhere. It can also be used in dessert, and I know this is where I lose people. But its texture really lends itself to producing a moist cake or a chewy Turkish delight candy, a recipe adapted from Chris Smith’s book The Whole Okra (pictured right).

We have a (not-so-secret) goal down here in the south to tell okra stories, convert so-called haters, and make okra a sexy addition to plates everywhere. It can also be used in dessert, and I know this is where I lose people. But its texture really lends itself to producing a moist cake or a chewy Turkish delight candy, a recipe adapted from Chris Smith’s book The Whole Okra (pictured right).

Chocolate Spiced Okra Bundt Cake

I am grateful for whoever first saw this plant and bravely decided that this hairy and spiny skinned silky vegetable was well worth cooking and eating. It’s a chef’s dream to have a product so versatile yet underutilized in the kitchen that allows our creativity to take over all reasoning. This is where we get to push limits and move needles forward. Is it too ambitious to think okra could become the next cauliflower, or is it just this southerner’s dream?